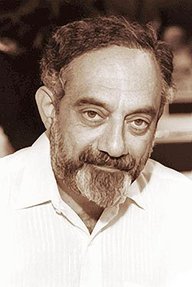

Fr. John Romanedes

Fr. John Romanedes The Boston Globe, April 8, 1965

I can foresee no way in which the teachings of the Orthodox Christian tradition could be affected by the discovery of intelligent beings on another planet. Some of my colleagues feel that even a discussion of the consequences of such a possibility is in itself a waste of time for serious theology and borders on the fringes of foolishness.

I am tempted to agree with them for several reasons.

As I understand the problem, the discovery of intelligent life on another planet would raise questions concerning traditional Roman Catholic and Protestant teachings regarding creation,

I can foresee no way in which the teachings of the Orthodox Christian tradition could be affected by the discovery of intelligent beings on another planet. Some of my colleagues feel that even a discussion of the consequences of such a possibility is in itself a waste of time for serious theology and borders on the fringes of foolishness.

I am tempted to agree with them for several reasons.

As I understand the problem, the discovery of intelligent life on another planet would raise questions concerning traditional Roman Catholic and Protestant teachings regarding creation,

the fall, man as the image of God, redemption and Biblical inerrancy.

First one should point out that in contrast to the traditions deriving from Latin Christianity, Greek Christianity never had a fundamentalist or literalist understanding of Biblical inspiration and was never committed to the inerrancy of scripture in matters concerning the structure of the universe and life in it. In this regard some modern attempts at de-mything the Bible are interesting and at times amusing.

Since the very first centuries of Christianity, theologians of the Greek tradition did not believe, as did the Latins, that humanity was created in a state of perfection from which it fell. Rather the Orthodox always believed that man [was] created imperfect, or at a low level of perfection, with the destiny of evolving to higher levels of perfection.

The fall of each man, therefore, entails a failure to reach perfection, rather than any collective fall from perfection.

Also spiritual evolution does not end in a static beatific vision. It is a never ending process which will go on even into eternity.

Also Orthodox Christianity, like Judaism, never knew the Latin and Protestant doctrine of original sin as an inherited Adamic guilt putting all humanity under a divine wrath which was supposedly satisfied by the death of Christ.

Thus the solidarity of the human race in Adamic guilt and the need for satisfaction of divine justice in order to avoid hell are unknown in the Greek Fathers.

This means that the interdependence and solidarity of creation and its need for redemption and perfection are seen in a different light.

The Orthodox believe that all creation is destined to share in the glory of God. Both damned and glorified will be saved. In other words both will have vision of God in his uncreated glory, with the difference that for the unjust this same uncreated glory of God will be the eternal fires of hell.

God is light for those who learn to love Him and a consuming fire for those who will not. God has no positive intent to punish.

For those not properly prepared, to see God is a cleansing experience, but one which does not move eternally toward higher reaches of perfection.

In contrast, hell is a static state of perfection somewhat similar to Platonic bliss.

In view of this the Orthodox never saw in the Bible any three story universe with a hell of created fire underneath the earth and a heaven beyond the stars.

For the Orthodox discovery of intelligent life on another planet would raise the question of how far advanced these beings are in their love and preparation for divine glory.

As on this planet, so on any other, the fact that one may have not as yet learned about the Lord of Glory of the Old and New Testament, does not mean that he is automatically condemned to hell, just as one who believes in Christ is not automatically destined to be involved in the eternal movement toward perfection.

It is also important to bear in mind that the Greek Fathers of the Church maintain that the soul of man is part of material creation, although a high form of it, and by nature mortal.

Only God is purely immaterial.

Life beyond death is not due to the nature of man but to the will of God. Thus man is not strictly speaking the image of God. Only the Lord of Glory, or the Angel of the Lord of Old and New Testament revelation is the image of God.

Man was created according to the image of God, which means that his destiny is to become like Christ who is the Incarnate Image of God.

Thus the possibility of intelligent beings on another planet being images of God as men on earth are supposed to be is not even a valid question from an Orthodox point of view.

Finally one could point out that the Orthodox Fathers rejected the Platonic belief in immutable archetypes of which this world of change is a poor copy.

This universe and the forms in it are unique and change is of the very essence of creation and not a product of the fall.

Furthermore the categories of change, motion and history belong to the eternal dimensions of salvation-history and are not to be discarded in some kind of eternal bliss.

Thus the existence of intelligent life on another planet behind or way ahead of us in intellectual and spiritual attainment will change little in the traditional beliefs of Orthodox Christianity.

First one should point out that in contrast to the traditions deriving from Latin Christianity, Greek Christianity never had a fundamentalist or literalist understanding of Biblical inspiration and was never committed to the inerrancy of scripture in matters concerning the structure of the universe and life in it. In this regard some modern attempts at de-mything the Bible are interesting and at times amusing.

Since the very first centuries of Christianity, theologians of the Greek tradition did not believe, as did the Latins, that humanity was created in a state of perfection from which it fell. Rather the Orthodox always believed that man [was] created imperfect, or at a low level of perfection, with the destiny of evolving to higher levels of perfection.

The fall of each man, therefore, entails a failure to reach perfection, rather than any collective fall from perfection.

Also spiritual evolution does not end in a static beatific vision. It is a never ending process which will go on even into eternity.

Also Orthodox Christianity, like Judaism, never knew the Latin and Protestant doctrine of original sin as an inherited Adamic guilt putting all humanity under a divine wrath which was supposedly satisfied by the death of Christ.

Thus the solidarity of the human race in Adamic guilt and the need for satisfaction of divine justice in order to avoid hell are unknown in the Greek Fathers.

This means that the interdependence and solidarity of creation and its need for redemption and perfection are seen in a different light.

The Orthodox believe that all creation is destined to share in the glory of God. Both damned and glorified will be saved. In other words both will have vision of God in his uncreated glory, with the difference that for the unjust this same uncreated glory of God will be the eternal fires of hell.

God is light for those who learn to love Him and a consuming fire for those who will not. God has no positive intent to punish.

For those not properly prepared, to see God is a cleansing experience, but one which does not move eternally toward higher reaches of perfection.

In contrast, hell is a static state of perfection somewhat similar to Platonic bliss.

In view of this the Orthodox never saw in the Bible any three story universe with a hell of created fire underneath the earth and a heaven beyond the stars.

For the Orthodox discovery of intelligent life on another planet would raise the question of how far advanced these beings are in their love and preparation for divine glory.

As on this planet, so on any other, the fact that one may have not as yet learned about the Lord of Glory of the Old and New Testament, does not mean that he is automatically condemned to hell, just as one who believes in Christ is not automatically destined to be involved in the eternal movement toward perfection.

It is also important to bear in mind that the Greek Fathers of the Church maintain that the soul of man is part of material creation, although a high form of it, and by nature mortal.

Only God is purely immaterial.

Life beyond death is not due to the nature of man but to the will of God. Thus man is not strictly speaking the image of God. Only the Lord of Glory, or the Angel of the Lord of Old and New Testament revelation is the image of God.

Man was created according to the image of God, which means that his destiny is to become like Christ who is the Incarnate Image of God.

Thus the possibility of intelligent beings on another planet being images of God as men on earth are supposed to be is not even a valid question from an Orthodox point of view.

Finally one could point out that the Orthodox Fathers rejected the Platonic belief in immutable archetypes of which this world of change is a poor copy.

This universe and the forms in it are unique and change is of the very essence of creation and not a product of the fall.

Furthermore the categories of change, motion and history belong to the eternal dimensions of salvation-history and are not to be discarded in some kind of eternal bliss.

Thus the existence of intelligent life on another planet behind or way ahead of us in intellectual and spiritual attainment will change little in the traditional beliefs of Orthodox Christianity.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed