Sinai became widely known, particularly in Europe, with the spreading of the fame and cult of St. Catherine. Symeon Metaphrastes contributed greatly in making the life of the Saint known to the laity when, in the 10th century, he wrote on “the martyrdom of the great Martyr and in the name of Christ victorious Saint Catherine”.

The high-born learned maiden had studied at the ethnic schools of that age philosophy, rhetorics poetry, music, physics, mathematics, astronomy and medicine. He beauty and amazing learning, her aristocratic birth and noble character did not prevent her form accepting Jesus Christ, “the heavenly spouse”, and she was baptized a Christian.

When in the beginning of the 4th century the emperor Maximum persecuted the Christians, Catherine publicly accused the emperor of worshipping idols and fearlessly confessed her Christian faith. To dissuade her, the emperor ordered fifty philosophers to discuss with Catherine and demolish her Christian arguments. Their attempt failed, and they, along with many others from the emperor’s closer circle, believed in Christ. When Maximus realized the futility of these efforts, he resorted to torture. He gave orders for the making of spiked wheels, but even this horrible torment failed to break the Saint, who was finally beheaded. Her body was then taken by angels and carried to the highest peak of Mount Sinai.

St. Catherine’s martyrdom and her relation to the Monastery of Sinai became known in the West when Symeon Metaphrastes brought relics of the Saint to Rouen and Treves, in France. The fame of the Saint spread rapidly in Europe and the Monastery of Sinai came to be known as the Monastery of St. Catherine. Generous gifts were sent to Sinai and estates were donated to the Monastery by European countries. “No Saint was loved in the West more than St Catherine”. Master painters-like Fra Angelico, Correggio, Rubbens, Titian and Murillo-immortalized on canvas scenes from the life and martyrdom of St. Catherine.

Saint Catherine, illustration from a Dutch Horologion, 1440-1460

The Saints’s cult and iconography had likewise spread in the East. She was portrayed in royal robes, wearing a crown and surrounded with objects alluding to her wisdom and martyrdom: a quill-pen, a globe, books, and a spiked wheel. To these the Byzantine hagiographers added depictions of Mount Sinai, Mount Horeb and the Mount of St. Catherine.

A great number of the Saints’s icons, often bordered with miniature scenes from her life and martyrdom, are kept to this day in Monastery.

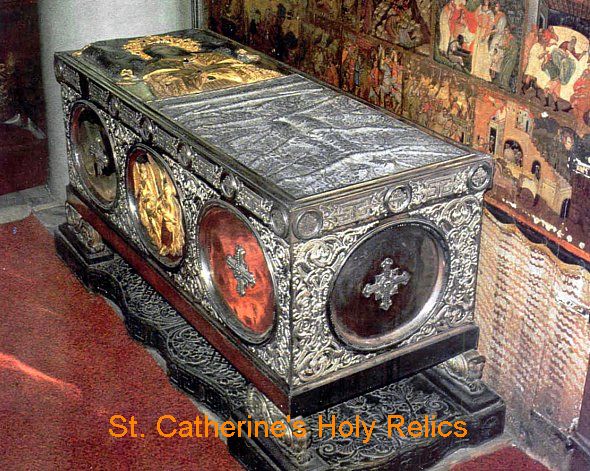

The Saint’s relics have been placed since early times in a marble chest. This larnax is mentioned in an itinerary dated 1231. In later years (1688) the royal family of Russia sent a silver casket, a gift of the Czars of Russia as recorded by the Cyrillic inscriptions, but the holy relics remained in the old marble chest.

From the late Byzantine age to the 20th century, whenever and wherever the Monastery of Sinai founded a metochi (dependency) it gave it the name of St. Catherine, The most active and famed Sinai Dependency of St. Catherine was the one at Herakleion in Crete, visited by numerous personalities of the Church, the arts and the letters.

Monastic life

Monastic life started very early in the region. Christian hermits began to gather at Sinai from the middle of the 3rd century. St. Antony’s retreat into the desert in the early 4th century prompted many hermits to settle at the foot of Mount Sinai and also of the other mountains, in particular Mount Serbal, where they led a life of strict spiritual and corporal discipline.

The solitary life and spiritual practice of the hermits went through great hardships in the 4th and 5th centuries. These were increased further by the persecutions they suffered from barbarian assailants “who sacrificed camels to their gods and did not refrain from slaughtering Christian monks”.

Saint Catherine, illustration from a Dutch Horologion, 1425-1450

The monk Ammonius of Egypt wrote A discourse upon the Holy Fathers slain on Mount Sinai and at Raitho. This was translated into the so-called “simple Greek” tongue (a mixture of vernacular and ancient Greek used in scholarly texts) by the monk Agapios Landos of Crete, who included it in the New Paradise. Another celebrated ascete and author of the 5th century, St. Nilus of Sinai, wrote Tales on the slaying of the monks on Mount Sinai and on the captivity of his son Theodoulos. This work was translated recently into “simple Greek” under the title Lament for Theodoulos by the theologian Athanasios Kottadakis.

However, the massacre and martyrdom of the Holy Fathers of Sinai and Raitho by the Hagarenes and the Blemmyes of Africa in Diocletian’s reign did not affect the development of monasticism in the Sinai desert. The anchorite population of South Sinai grew and the fame of many of the hermits spread to both East and West.

Small monastic communities were formed quite early, especially in the area of Mount Horeb, the site of the Burning Bush and the valley of Faran (ancient Pharan). The anchorites lived in caves, stone-built cells and huts, spending their days in silence, prayer and sanctity.

It is reported that in A.D 330, in response to a request by the ascetics of Sinai, the Byzantine empress Helena (St. Helen) ordered the building of a small church consecrated to the Holy Virgin at the site of the Burning Bush and of a fortified enclosure where the hermits could find refuge from the incessant attacks of primitive pagan nomadic tribes.

Saint Catherine, mosaic from Hosios Loukas Monastery in Fokida, Greece, 11th Century

From the 4th century onwards South Sinai became a place of pilgrimage visited by many pilgrims from far-away lands. A manuscript discovered in 1884 relates that in A.D. 372-374 Aetheria, a noblewoman from Spain accompanied by the retinue of clerics, journeyed to Sinai to visit the hermits. She found a small church on the summit of Mount Sinai, another one on Mont Horeb and a third one at the site of the Burning Bush, near which there was a fine garden with plenty of water.

Aeatheria’s account revealed the expansion of monasticism in the Sinai desert. By the middle of the 5th century the growing population of hermits was apparently headed by a dignitary, mentioned as Bishop of Pharan. With the passing of time this office and title were taken over by the Bishop of Sinai. On more than one occasion the monks of Sinai struggled for the consolidation of the Orthodox faith by taking an active part in the controversies between Church and heretics.

When monasticism in the Sinai peninsula expanded, men of great moral stature emerged from this arid and desolate place. Apparently in response to a request by the Sinaites, Justinian, emperor of Byzantium, founded a magnificent church, which he enclosed within walls strong enough to with stand attacks and protect the monks against eventual raids.

The historian Procopius in his work On Buildings has preserved useful information on the church and the “very strong fortress” built by Justinian.

Henceforth, an new glorious page begins in the holy history of Sinai.

The fortress of Justinian

The fortified enclosure of the Monastery is built of rectangular hewn blocks of hard granite. It is somewhat off-square in shape, its sides measuring 75 m. on the west, 88 m. on the north, 75 m. on the east and 80 m. on the south. The height varies from 8 m. on the south to 25 m. on the north side, and the thickness of the granite wall ranges from 2 to 3 m., depending on the space needed for towers, crypts etc. The south wall decorated on the outer side with ancient cross symbols and other stone carvings, faces towards Mount Sinai and is the one that has been best preserved. The north wall has suffered the worst damages and has been repaired several times over the centuries, even by Napoleon’s army in 1798-1801.

Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai. Photo: Peter Brubacher, used with permission

The ancient gate, with a machicolation above it to strengthen its defence, is on the west side of the fortress. Today this gateway is closed, and another old entrance is in use, secured every night by three iron-bound doors.

The monk’s cells and other structures were built along the inner sides of the fortified enclosure. The irregular and sloping ground was leveled by constructing solid arches and barre-vaults, upon which the monk’s dwellings and other buildings were raised.

The Monastery’s Church (Katholikon), also built at that time of massive granite blocks, is a three-ailed basilica with narthex. It measures 40 m. in length and 19.20 m. in width, including the chapels it incorporates behind the sanctuary apse, i.e. the Chapel of the Burning Bush and the terminal chapels dedicated to St. James and to the Holy Fathers of Sinai. The naos proper of the Katholikon measures 25 m. in length and 12m in width. It is divided into three aisles by colonnades of six monolithic granite columns, each carrying a different capital ornamented with cross, lamb, plant and fruits motifs. The columns have been covered with a coating so that the beautiful colour of the granite stone is no longer visible.

The holy relics of Saint Catherine. Monastery of Sinai

In the 18th century, during the time when Cyril of Crete was Archbishop of Sinai, the ancient timber roof of the katholikon was covered with a horizontal wooden coffered ceiling, which was painted blue and adorned with a multitude of golden stars. The side walls are pierced by two rows of windows-eight double-arched windows and seven rectangular ones. The level of the holy bema is higher than that of the nave. The templon separating theses two ares of the church is composed of marble panels below and a wood carved iconostasis above, reaching to the ceiling with the so-called Lypera (icons of the Virgin and St. John standing on either of the Crucifix). The iconostasis is of the early 17th century, made in 1612 in the Monastery’s dependency of Crete at the time of the Archbishop Lavrentios.

The original splendidly carved doors leading from the narthex to the naos proper are made of Lebanon cedar wood and date from the 6th century. The portal of the narthex was made by the Crusaders in the 11th century.

The church is decorated with rare and priceless icons of various periods.

Source: The Monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai, published by St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai, 1985

pemptousia.gr

When in the beginning of the 4th century the emperor Maximum persecuted the Christians, Catherine publicly accused the emperor of worshipping idols and fearlessly confessed her Christian faith. To dissuade her, the emperor ordered fifty philosophers to discuss with Catherine and demolish her Christian arguments. Their attempt failed, and they, along with many others from the emperor’s closer circle, believed in Christ. When Maximus realized the futility of these efforts, he resorted to torture. He gave orders for the making of spiked wheels, but even this horrible torment failed to break the Saint, who was finally beheaded. Her body was then taken by angels and carried to the highest peak of Mount Sinai.

St. Catherine’s martyrdom and her relation to the Monastery of Sinai became known in the West when Symeon Metaphrastes brought relics of the Saint to Rouen and Treves, in France. The fame of the Saint spread rapidly in Europe and the Monastery of Sinai came to be known as the Monastery of St. Catherine. Generous gifts were sent to Sinai and estates were donated to the Monastery by European countries. “No Saint was loved in the West more than St Catherine”. Master painters-like Fra Angelico, Correggio, Rubbens, Titian and Murillo-immortalized on canvas scenes from the life and martyrdom of St. Catherine.

Saint Catherine, illustration from a Dutch Horologion, 1440-1460

The Saints’s cult and iconography had likewise spread in the East. She was portrayed in royal robes, wearing a crown and surrounded with objects alluding to her wisdom and martyrdom: a quill-pen, a globe, books, and a spiked wheel. To these the Byzantine hagiographers added depictions of Mount Sinai, Mount Horeb and the Mount of St. Catherine.

A great number of the Saints’s icons, often bordered with miniature scenes from her life and martyrdom, are kept to this day in Monastery.

The Saint’s relics have been placed since early times in a marble chest. This larnax is mentioned in an itinerary dated 1231. In later years (1688) the royal family of Russia sent a silver casket, a gift of the Czars of Russia as recorded by the Cyrillic inscriptions, but the holy relics remained in the old marble chest.

From the late Byzantine age to the 20th century, whenever and wherever the Monastery of Sinai founded a metochi (dependency) it gave it the name of St. Catherine, The most active and famed Sinai Dependency of St. Catherine was the one at Herakleion in Crete, visited by numerous personalities of the Church, the arts and the letters.

Monastic life

Monastic life started very early in the region. Christian hermits began to gather at Sinai from the middle of the 3rd century. St. Antony’s retreat into the desert in the early 4th century prompted many hermits to settle at the foot of Mount Sinai and also of the other mountains, in particular Mount Serbal, where they led a life of strict spiritual and corporal discipline.

The solitary life and spiritual practice of the hermits went through great hardships in the 4th and 5th centuries. These were increased further by the persecutions they suffered from barbarian assailants “who sacrificed camels to their gods and did not refrain from slaughtering Christian monks”.

Saint Catherine, illustration from a Dutch Horologion, 1425-1450

The monk Ammonius of Egypt wrote A discourse upon the Holy Fathers slain on Mount Sinai and at Raitho. This was translated into the so-called “simple Greek” tongue (a mixture of vernacular and ancient Greek used in scholarly texts) by the monk Agapios Landos of Crete, who included it in the New Paradise. Another celebrated ascete and author of the 5th century, St. Nilus of Sinai, wrote Tales on the slaying of the monks on Mount Sinai and on the captivity of his son Theodoulos. This work was translated recently into “simple Greek” under the title Lament for Theodoulos by the theologian Athanasios Kottadakis.

However, the massacre and martyrdom of the Holy Fathers of Sinai and Raitho by the Hagarenes and the Blemmyes of Africa in Diocletian’s reign did not affect the development of monasticism in the Sinai desert. The anchorite population of South Sinai grew and the fame of many of the hermits spread to both East and West.

Small monastic communities were formed quite early, especially in the area of Mount Horeb, the site of the Burning Bush and the valley of Faran (ancient Pharan). The anchorites lived in caves, stone-built cells and huts, spending their days in silence, prayer and sanctity.

It is reported that in A.D 330, in response to a request by the ascetics of Sinai, the Byzantine empress Helena (St. Helen) ordered the building of a small church consecrated to the Holy Virgin at the site of the Burning Bush and of a fortified enclosure where the hermits could find refuge from the incessant attacks of primitive pagan nomadic tribes.

Saint Catherine, mosaic from Hosios Loukas Monastery in Fokida, Greece, 11th Century

From the 4th century onwards South Sinai became a place of pilgrimage visited by many pilgrims from far-away lands. A manuscript discovered in 1884 relates that in A.D. 372-374 Aetheria, a noblewoman from Spain accompanied by the retinue of clerics, journeyed to Sinai to visit the hermits. She found a small church on the summit of Mount Sinai, another one on Mont Horeb and a third one at the site of the Burning Bush, near which there was a fine garden with plenty of water.

Aeatheria’s account revealed the expansion of monasticism in the Sinai desert. By the middle of the 5th century the growing population of hermits was apparently headed by a dignitary, mentioned as Bishop of Pharan. With the passing of time this office and title were taken over by the Bishop of Sinai. On more than one occasion the monks of Sinai struggled for the consolidation of the Orthodox faith by taking an active part in the controversies between Church and heretics.

When monasticism in the Sinai peninsula expanded, men of great moral stature emerged from this arid and desolate place. Apparently in response to a request by the Sinaites, Justinian, emperor of Byzantium, founded a magnificent church, which he enclosed within walls strong enough to with stand attacks and protect the monks against eventual raids.

The historian Procopius in his work On Buildings has preserved useful information on the church and the “very strong fortress” built by Justinian.

Henceforth, an new glorious page begins in the holy history of Sinai.

The fortress of Justinian

The fortified enclosure of the Monastery is built of rectangular hewn blocks of hard granite. It is somewhat off-square in shape, its sides measuring 75 m. on the west, 88 m. on the north, 75 m. on the east and 80 m. on the south. The height varies from 8 m. on the south to 25 m. on the north side, and the thickness of the granite wall ranges from 2 to 3 m., depending on the space needed for towers, crypts etc. The south wall decorated on the outer side with ancient cross symbols and other stone carvings, faces towards Mount Sinai and is the one that has been best preserved. The north wall has suffered the worst damages and has been repaired several times over the centuries, even by Napoleon’s army in 1798-1801.

Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai. Photo: Peter Brubacher, used with permission

The ancient gate, with a machicolation above it to strengthen its defence, is on the west side of the fortress. Today this gateway is closed, and another old entrance is in use, secured every night by three iron-bound doors.

The monk’s cells and other structures were built along the inner sides of the fortified enclosure. The irregular and sloping ground was leveled by constructing solid arches and barre-vaults, upon which the monk’s dwellings and other buildings were raised.

The Monastery’s Church (Katholikon), also built at that time of massive granite blocks, is a three-ailed basilica with narthex. It measures 40 m. in length and 19.20 m. in width, including the chapels it incorporates behind the sanctuary apse, i.e. the Chapel of the Burning Bush and the terminal chapels dedicated to St. James and to the Holy Fathers of Sinai. The naos proper of the Katholikon measures 25 m. in length and 12m in width. It is divided into three aisles by colonnades of six monolithic granite columns, each carrying a different capital ornamented with cross, lamb, plant and fruits motifs. The columns have been covered with a coating so that the beautiful colour of the granite stone is no longer visible.

The holy relics of Saint Catherine. Monastery of Sinai

In the 18th century, during the time when Cyril of Crete was Archbishop of Sinai, the ancient timber roof of the katholikon was covered with a horizontal wooden coffered ceiling, which was painted blue and adorned with a multitude of golden stars. The side walls are pierced by two rows of windows-eight double-arched windows and seven rectangular ones. The level of the holy bema is higher than that of the nave. The templon separating theses two ares of the church is composed of marble panels below and a wood carved iconostasis above, reaching to the ceiling with the so-called Lypera (icons of the Virgin and St. John standing on either of the Crucifix). The iconostasis is of the early 17th century, made in 1612 in the Monastery’s dependency of Crete at the time of the Archbishop Lavrentios.

The original splendidly carved doors leading from the narthex to the naos proper are made of Lebanon cedar wood and date from the 6th century. The portal of the narthex was made by the Crusaders in the 11th century.

The church is decorated with rare and priceless icons of various periods.

Source: The Monastery of St. Catherine on Mount Sinai, published by St. Catherine’s Monastery at Sinai, 1985

pemptousia.gr

RSS Feed

RSS Feed